In 2018, the Colombian anthropologist Arturo Escobar remarked:

We are facing modern problems for which there are no longer modern solutions

What he’s referring to is that the worsening ecological crises, created through Western knowledge systems, cannot be solved by Western knowledge systems despite being widely considered ‘advanced’ and ‘modern’.

This involves the mindset and understandings of the world that Western science is rooted in and maintains. Another way to put it, in the words of Ajay Parasram and Lisa Tilley is that:

Colonial science alone is ill-equipped to solve colonial problems

Colonial science? Knowledge is not created or maintained in a vacuum, it is a product of particular contexts, norms, influences, and values; “The truth is that facts and frameworks reflect the worldviews and truths of their creators” as Amber Huff and Nathan Oxley phrase it. And most people in the world, before colonial invasion at least, do not share the same worldviews and truths as Westerners. Western science teaches us that these alternate systems are incorrect, for example animist societies who *know* how the world is and value it based on spiritual relations (read more here).

Nature conservation is at the forefront of colonial science. The majority of nature conservation remains centred on the creation of protected areas, built to keep ‘nature’ in and people out. In the most extreme these involve the eviction and brutalising of indigenous and local communities who are in the way of nature (such as that ongoing around Messok-Dja in Congo). In the least extreme cases protected areas may involve some level of so-called ‘sustainable use’ by local people and perhaps even co-management or indigenous protected areas. But the concept of protected areas itself is increasingly being criticised because it is inextricably dependent on a separation between people and ‘nature’, when actually the majority world (those outside of the West) see no such dividing lines at all.

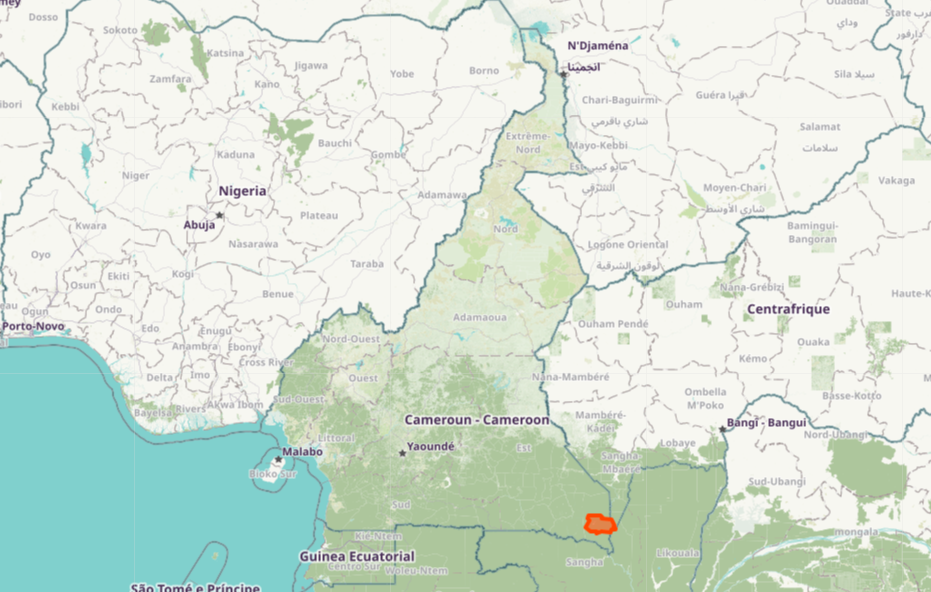

Lobéké National Park in south-eastern Cameroon is a prime example.

The park was created in 1999 to protect the rich biodiversity of the region from poaching. Lines were drawn on maps and eco-guards were employed to conduct armed patrols of the forest. Unfortunately, despite claims that local Baka hunter-gatherer and Bangando communities were consulted and gained access to the park which was ‘For them a dream came true!’, in reality access has been heavily restricted resulting in cultural destruction, and the deterioration of livelihoods thereby forcing many into the illegal wildlife trade. Unsurprisingly, this has led to increased poaching and fewer and fewer animals.

Some Baka communities have been instructed to apply for permission before entering the forest by filling in paperwork, but the vast majority of people are illiterate and cannot wait to receive permission before going in search of food, the permit itself only lasting for a couple of weeks before having to renew it again. Most worryingly, serious cases of abuse and violence by eco-guards have been recorded towards Baka people surrounding the park, including beatings, torture, destruction of villages, and confiscation of food. Conservation can of course never be successful or sustainable when it is goes hand-in-hand with human rights abuses. Ironically, it is the Baka and their ancestors who have inhabited these forests for many millennia and, through their practices and knowledge, have played a part in making the forest as rich as it is today.

In 2019, a memorandum of understanding (MoU) was signed between the Baka of this region and the Ministry of Forestry and Wildlife. The deal was that the Baka will be allowed access to the park in order to hunt, fish, forage and carry out cultural activities, but only if following strict restrictions on size of prey, hunting equipment and many other things.

Human rights organisations have criticised the MoU for it’s vagueness on what actual rights the Baka will have with regard to accessing the park, and that communication with communities has been so poor that they often ‘claimed to know nothing of the MoU (some not even knowing what “MoU” meant)’. The whole idea of an MoU itself as a solution in this case should be put into context when considering more fundamentally that this forest has been stolen from local people (‘green grabbing’) who need it to survive, despite the root causes of ivory trafficking, pangolin smuggling, and logging being elsewhere.

In any case, the MoU exists and the task now is to properly monitor it. In this vein, WWF, who supports the government in managing Lobéké, invited me to initiate Sapelli citizen science projects alongside the Baka of Lobéké. Whilst being initially hesitant to work in this controversial and problematic context, I decided that this was an opportunity to initiate change, whereby the voices and values of the Baka could be taken seriously.

Maximising the bottom-up design of the project and the sharing of knowledge between Baka communities, I asked Mangombe, a friend from my primary fieldwork village, if he’d like to join me in the new WWF work. He hastily agreed, excited about meeting many new Baka families in a different region and learning medicines of the forest that are new to him.

We set off on the 5-day journey from Bemba village on the edge of the Ngoyla-Mintom forests to the Lobéké forests of the East.

Contrary to the way conservation projects normally work, minimal planning and design was done before visiting communities in order to promote local leadership. The Sapelli technology was not initially mentioned in village meetings at all – doing so may lead to communities joining the project simply because they want to use a smartphone. Instead, we sat down and asked communities about their forest – what concerns they have, what their current situation is like, how the forest has changed, how intact their traditions are, what their relationships are like with ministry eco-guards, WWF, non-Baka communities.

These conversations revealed all sorts of interesting insights: problems with accessing the forest due to abusive eco-guards and absurd requirements to apply for written permission; conflict with safari reserves who keep the Baka out by employing heavily-armed personnel (who shoot first and ask questions later); anger over logging companies who are cutting down the forest, for which the Baka see no benefits, and includes important medicinal and fruiting trees; wildlife traffickers that arrive, coercing some local people to help, and smuggle animals and trophies away by tipping off officials; concerns by elders that Baka ecological knowledge and cultural heritage is vanishing and failing to be passed on to the next generation, amongst many other things. Two villages told us of concerted efforts by government guards to destroy Baka culture by threatening communities to stop calling the ancient and most powerful spirit of the forest – ‘Ejengi‘. This was shocking to for us to hear because of the fundamental role Ejengi plays in male initiation, teaching boys how to walk in the forest, identify medicines, hunt animals, and other knowledge to survive, and also his role in mediating conflicts and at other times of distress (watch this for more). “We need to have Ejengi in our village” the women told me.

Sapelli projects emerged from these concerns, and with constant dialogue with the communities (if you’re not familiar with Sapelli, see here). Sapelli was not presented as a solution to all the problems, but more so as a tool which could help with addressing specific problems which we identified together: increasing access to the forest by mapping important resources (fruit trees, honey, wild yam, fishing and hunting sites, and medicinal trees; a requirement for access within the MoU), reporting wildlife poaching, documenting instances of violence and abuse, and recording where animals eat and damage crops (human-wildlife conflict).

At a meeting on the MoU there was a change of tune in regard to Ejengi. WWF and the ministry decided that the Baka should be allowed to hunt elephants in order to practice the Ejengi ceremony, but restricted to a maximum of one per year for several villages grouped together. In order for this to work, they said, it would have to be carefully monitored; but how do you carefully monitor a forest spirit? Sapelli, the Baka decided, could play a part in this by alerting authorities as to when Ejengi has arrived and whether the hunting of an elephant may be necessary.

One of the best parts of a bottom-up approach is the tendency to produce unexpected outcomes – the mapping of Ejengi, but also the youths in one village who proposed that Sapelli could help them map potential sites for football pitches (though later changed their minds).

It all hinges on the process of free, prior, and informed consent (FPIC): being honest with communities about the possible advantages and risks of the projects, and ensuring that proper understanding is behind their decision to accept or deny the projects. Having these conversations relies upon trust, and, having worked with the Baka in Cameroon since 2016, I’ve learnt how this can be achieved. Speaking the Baka language is the most impactful, and I’ve learnt it through living in Mangombe’s village: hard work but opens up so much. The WWF staff accompanying me included two Baka employees, meaning that for many meetings and also amongst ourselves we would be speaking in Baka. Staying overnight in each community where we would share food, hear stories and histories, and get to know people more genuinely was invaluable.

The Sapelli software is made up of icons in order to include those who cannot read and write (such as the Baka), and I’ve found that if these icons are designed by each community themselves, not only does the software make much more sense, but community members feel a sense of ownership over the technology. This process of locally-led ‘co-design’ is an important part of trying to decolonise research.

Training in how to use the smartphones was done with a self-selected team within each community over two or three sessions in the forest, during which questions were encouraged and the FPIC process continued. Communities decide for themselves how they will manage the phone – who will keep and charge it and how they will share it -, where exactly their data will go and who will have access to it, and for what purpose. It’s all well and good to involve indigenous peoples in participative, innovative projects, but if they do not have the opportunity to decide on who has access to their data and for what reason, are these really so different from top-down, colonial methodologies?

The primary use of Sapelli in all five villages centres on helping to regain access to the forest, both the national park, and its periphery – a forest taken from them, but in which their ancestors thrived and their identities and spiritual world still depend. But this project too requires strong collaboration with outsiders (WWF, the ministry, ExCiteS) in order for the data to change things, and it’s us outsiders who remain in the position to actually take actions or not.

So, whilst this is a positive step, I don’t think it goes far enough. Conservation must shift towards autonomous management, whereby communities themselves receive the funding (perhaps in the form of organisations or associations), and protect landscapes as a part of a complex web of social-ecological connections. Indigenous protected areas, like those in Australia, go part of the way, but so-called ‘biocultural heritage territories‘ must be the objective of all conservationists – “Their main goal is holistic wellbeing, rather than conservation, but holistic wellbeing means the wellbeing of both people and nature, and results in conservation as the outcome of an autonomous process. This reflects Indigenous peoples’ holistic worldview that biodiversity and culture — or nature and people — are inextricably linked and cannot be separated.” This has also been termed ‘flourishing diversity‘, which stresses the necessity of learning from indigenous wisdom traditions.

Such ideas of conservation are likely to differ hugely from those in the West and the average WWF supporter. ‘Modern’ solutions must become increasingly about local, alternative, decolonised solutions, which embrace other knowledges and world-views on an equal level, which Sapelli and similar tools can certainly help with.

I’m sure these will, in most cases, seem radical. But to those who live within the majority of the world’s conservation hotspots and are on the frontline of ecological and cultural crisis, such as the Baka, these ideas are not at all new and are practiced through everyday life. They have, therefore, always been modern.

Acknowledgment to Mangombe Felix, Yvette Mongondji, and Bibi, without whom this project would not have materialised. Endlessly hard-working, intelligent, and generous

Funded by the European Research Council Horizon 2020 and WWF

1 Comment