Messaging is popular, but mapping is not. Mapping is mainly done by professionals or machines, and this is a problem because there is so much ground information that can only be captured by local people in real-time and at scale. The ground data gap is huge, and this translates into poorly informed decision-making. To bridge this gap, mapping needs to become popular, and to popularise mapping, mapping needs to go where people are in the digital environment, i.e. in messaging apps.

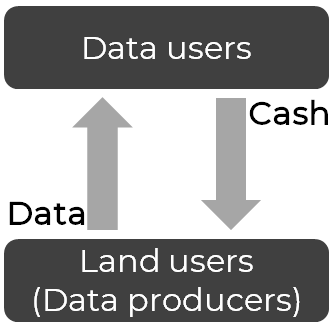

In a global climate crisis context, this lack of locally relevant ground information is a problem, but also an opportunity to reduce poverty. How? On the one hand, instead of investing all ground data collection resources to paying professional surveyors/enumerators who often need to travel to collect ground information, some of these resources could be allocated to repurpose professional data collectors and to remunerate local people for collecting data. On the other hand, instead of investing vast amounts of resources in monitoring the ground from space, some of these resources could be allocated to monitoring the ground from the ground. Data users can bridge the poverty gap by paying land users for bridging the ground data gap.

Why data-cash exchanges? Among other reasons, because there is growing evidence that direct cash transfers are effective to reduce poverty and increase engagement in data collection, especially at the margins. If mapping becomes popular, new (de)centralised business ecosystems connecting those who can produce ground information and those who need it might emerge across scales, making development more evidence-driven, decentralised and sustainable.

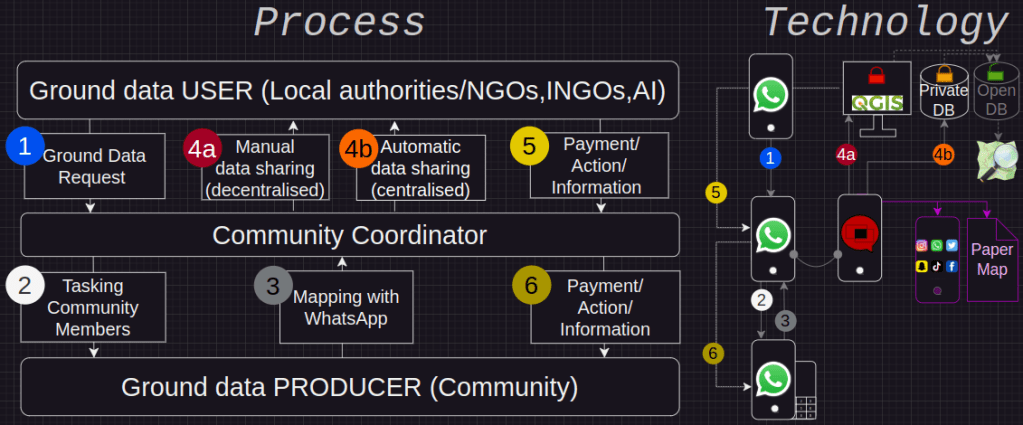

Process and technology

This article briefly reports on an ongoing pilot project in rural Ethiopia, where Nyangatom agro-pastoralist communities are being remunerated for updating the census themselves and mapping the condition of the water infrastructure (e.g. manual water pumps, irrigation pumps, etc.). For more information about the context and the previous pilot projects that this project builds upon, see Stevenson et al. (2022) and Moreu et al. (2022). The six-step process is as follows:

Step 1: The ground data user (e.g. local government, NGO, UN official) sends a WhatsApp message and instructions to the community coordinators to collect information (e.g. ‘map all the water pumps that are not operational’).

Step 2: Every community coordinator creates a WhatsApp group to mobilise community members for data collection.

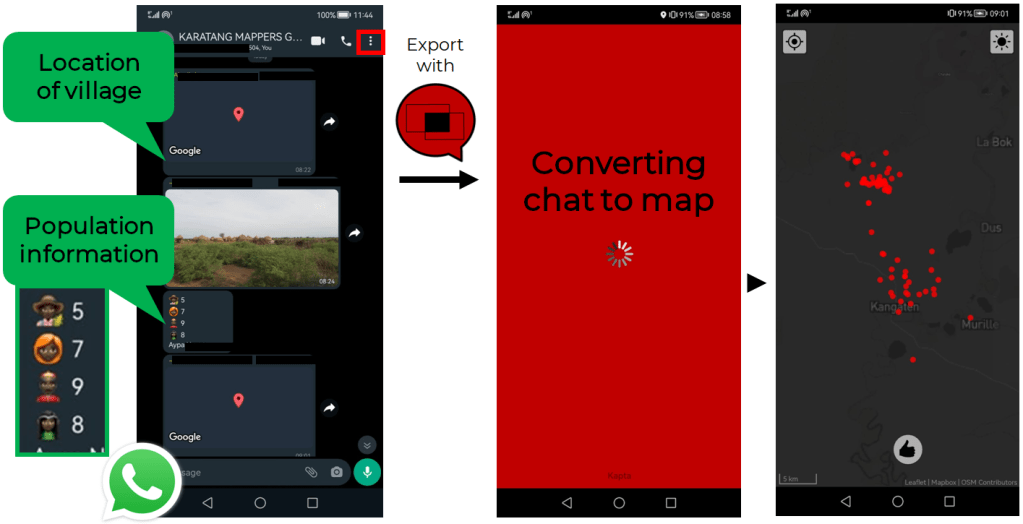

Step 3: The community members collect and share the data in the WhatsApp group and monitor the map contributions of others (i.e. peer data validation). Three steps are required to collect ground information with WhatsApp: Share the location, take a picture, and describe it.

Step 4: So far, the only tool that is needed is WhatsApp. At this stage, the community coordinator converts the WhatsApp group’s chat into a map using 👉 this platform.

Once the app converts the chat into a map, the community coordinator can share the map image in social media, print the map and/or share the map data with data users in a decentralised or centralised way:

4a) In a decentralised way by using only the mobile app and WhatsApp (i.e. no central spatial database). For instance, by sharing the file (GeoJSON) with a local map expert who has the skills to process it in a GIS and produce a map report e.g. for government officials or for local or international NGOs operating in the area.

4b) In a centralised way by selecting the ‘YES’ switch (see figure below), in which case the map data is automatically sent from the app to a private-before-open database, currently managed by UCL researchers. A direct connection from the mobile app to an open database has not been implemented to promote decentralised and centralised data-cash exchanges and to ensure that data is made open where appropriate.

It is worth noting that Google Maps in this area is mainly empty, as this is the case in most rural areas of the world. Global maps and planetary-scale monitoring systems need to integrate open ground data into their machine learning models to produce information that is relevant across scales.

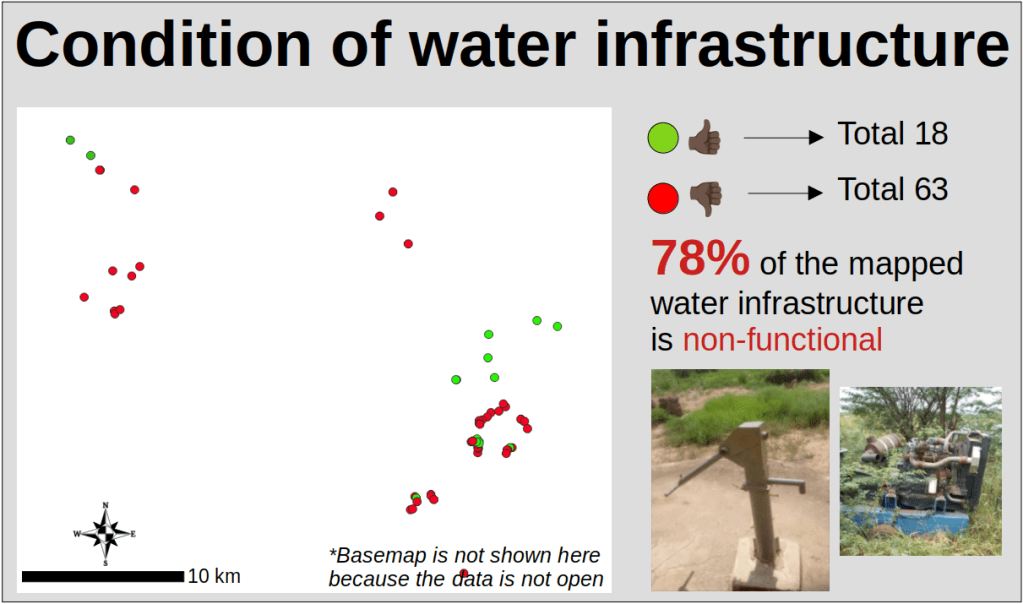

Step 5: The ground data users pay the community coordinator what they agreed, and produce and share a report summarising the validated ground information collected by locals. Advances in generative AI can play a role here in democratising spatial data processing to extract key information from a map/geo-chat and assist in the production of a report. See below example report for the Ethiopia project – lack of green dots means that people living in the area do not have access to clean water or need to walk long distances to get it.

Step 6: The community coordinator pays the community members what they agreed using cash, mobile money etc.

The diagram below illustrates this six-step process and the technology used in each step.

Data quality

How is data quality ensured? Using the wisdom of the crowd, which are techniques that are based on over a decade of studying data quality in citizen science and crowdsourcing. In short, the more people contributing to a map, the better the map, because given the right conditions, the errors compensate each other. Put differently, the more WhatsApp groups to map the same thing, the better the resulting community map.

The quality of polygon data collection (e.g. farming and grazing areas) was briefly presented in the article “Wisdom of the Crowd in the Age of AI: Water” and was explained in depth in Moreu (2024, pp. 225-247). The point data collection that started in April 2024 is ongoing and the data quality results will be published after field data validation and analysis. So far, six WhatsApp groups have mapped around 80 items of water infrastructure and their condition (e.g. ‘this water pump is not working’) and around 100 villages with demographic information (number of adults male, adults female, kids male, kids female).

How is the data validated? By professional data collectors who go to the field to validate random locations. For instance, if the community maps 100 villages, the validator might visit 10 villages; if the validator’s data match the community-generated data in 9 villages, then the entire dataset (i.e. the population of 100 villages) can be considered as 90% accurate. With this approach, the professional data collectors only need to visit 10% of the villages, not all of them.

Impact

What impact might this approach have? So far, the maps have had no discernible impact, but the trial currently underway in Ethiopia may change this. As a partner in government told us:

“If the local community demonstrates that they can collect good information, we might allocate resources to remunerating them for collecting any kind of information, not only population and water pumps information.”

This statement is important because it is a step towards the emergence of new (de)centralised business ecosystems connecting those who can produce ground information and those who need it. This could open up opportunities for remuneration not only for community coordinators and communities in general, but also for enumerators and volunteer mappers (e.g. OpenStreetMap mappers) who might play a crucial role in figuring out what data is valuable, mobilising community coordinators and processing ground data for local and global data users and decision makers.

Finally, connecting users and producers (of ground information) is about trust, a trust chain. Data users need to trust data producers, and data producers and intermediaries need to trust those whom they share the data with. For instance, the community trusts the community coordinator, who is trusted by the local government, who trusts the local map expert, who is trusted by the global mapping community, because the crowd can be wise. How wise can we be? In collective intelligence, just like in artificial intelligence, is it just about volume of data? These are open questions that require further research…. While research progresses, WhatsApp is increasingly becoming ubiquitous because, among other reasons, it connects people who trust each other. To popularise mapping, mapping needs to go to messaging: WhatsApp Maps.

by Marcos Moreu, Jed Stevenson, Dessalegn Tekle, Fabien Moustard, Claire Ellul, Muki Haklay.

With thanks to our Nyangatom collaborators, the UCL’s Centre for Advanced Research Computing (UCL ARC) for improving the software and to CARTO, Planet and the European Space Agency for providing free access to cloud services and satellite imagery since this project started in 2021.

This project has received funding from the European Research Council, Formas, UCL Grand Challenges-Food Security Special Issue, UCL Innovation & Enterprise and UCL Grand Challenges-Responsible Innovation Award.