By Simon Hoyte & Jerome Lewis

The world is waking up to the deep connection between human, animal, plant, and environmental health.

The concept of ‘One Health’, coined by the vet William Karesh in 2003, is now a hot topic, rising high on international agendas after the COVID-19 pandemic. One Health simply refers to how ‘the health of humans, domestic and wild animals, plants, and the wider environment (including ecosystems) are closely linked and interdependent’ (WHO).

‘By linking humans, animals and the environment, One Health can help to address the full spectrum of disease control – from prevention to detection, preparedness, response and management – and contribute to global health security’.

But One Health is much more than disease control, it concerns the wellbeing of environments and all their inhabitants. It is about plant and animal health, food and water security, cultural and spiritual ties to animals, plants, and the environment, addressing human rights violations and much more.

What is striking about the concept of One Health is that is far predates William Karesh. Indigenous and traditional societies all over the world know that human health and wellbeing is and has always been in a constant relationship with animal, plant and ecosystem health. Amongst many cultures the sense of this is so strong that animals, plants, spirits, environmental features or even the Earth herself are considered persons just as humans are, and if these beings are in a bad condition, so too will humans be.

For hunter-gatherers, this relationship could not be more important. The Baka, with whom Simon worked in southern Cameroon for his PhD, cannot envisage a good or healthy life without the forest. “If the Baka don’t have the forest, the life of the Baka will not go on” one elder told him. This elder is fully aware of the cooling effect of the forest and how hot, dry, drought conditions arrive with deforestation. But he is also referring to numerous other aspects – destruction of forest means fewer animals to hunt and fish to catch, less forest honey, fruits, and mushrooms to eat, drying up of valuable drinking water sources, the driving away of forest and ancestral spirits who inhabit the forest. The primary mode of healthcare for Baka are forest remedies – making medicine out of tree bark, leaves, roots, fruits, and berries. “There is bark to heal you. The bark, the roots, all the leaves that we see there, they heal!” Simon’s friend Mangombe told him. How can the Baka be healthy without the forest?

The Baka and other BaYaka hunter-gatherers are disillusioned with the way forest conservation has, and in many cases continues, to be done. “When the Baka controlled the forest, everything is living – the fish live, the elephants live. In Baka camps the forest is in good condition, many different things can be found living in the forest there.” Mangombe told Simon. Mongemba, a Mbendjele man from Congo, notes “Now it’s all finished, all finished! Now there is just sadness! We have such hunger. Fear, such fear! The boys are frightened to go in the forest. It’s the eco-guards [conservation patrols]. They accuse you: ‘You killed an elephant, you go to prison’. Fear has entered our boys, this is the root of our problem” (Hoyte 2025; Lewis 2016).

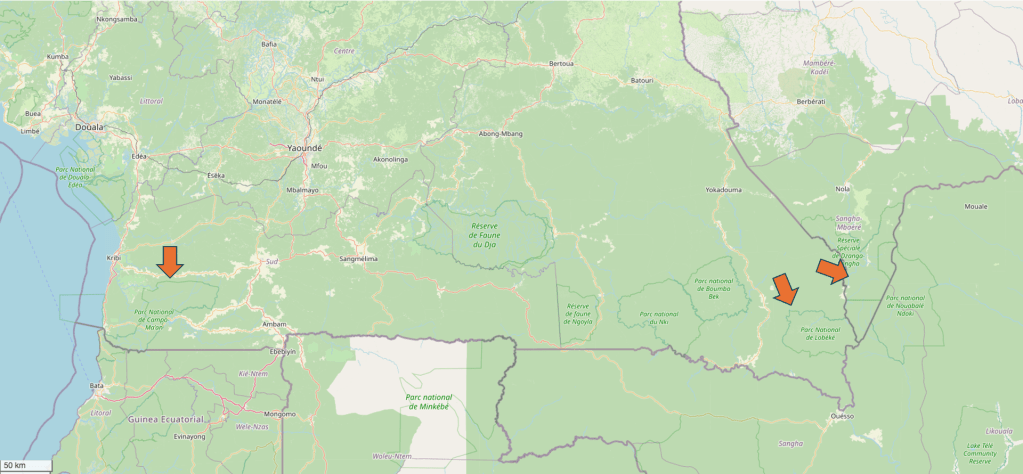

Beginning last October, we initiated a new project for the Extreme Citizen Science group titled ‘In.For.Bio’. Working alongside nine consortium partners – Food and Agricultural Organisation of the UN, Helmholtz Institute for One Health (Germany), Project Bwanga (Congo), International Institute for Tropical Agriculture (Nigeria), Congo Basin Institute (Cameroon), Centre pour l’Environnement et le Développement (Cameroon), and WWF Germany, WWF Cameroon, and WWF CAR – we have formed a 6-year-long initiative centred on One Health in the Congo Basin funded by the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Climate Action, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMUKN). Under this initiative, we will work with three different hunter-gatherer groups across three landscapes: the Campo Ma’an landscape and Lobeke landscape in Cameroon, and Dzanga-Sangha in Central African Republic (CAR) to develop a One Health approach to caring for the forest.

Whilst previously hesitant to collaborate with WWF due to a record of poor community consultation and involvement in human rights abuses in this region, the partner WWF offices now expressed a clear desire to transform their engagement with communities and work towards valorising Indigenous knowledge systems. Our work will be to help them to achieve this.

Encouraged by a collective acceptance that protected areas for conservation in the region are not achieving their stated aims, with steady declines in biodiversity demonstrating the ineffectiveness of current biodiversity safeguards, the militarisation of conservation leading to social abuse, and forced exclusion from traditional forest areas causing cultural erosion, the project aims to shift the concept of environmental protection towards human and environmental health. This may sound odd to anyone who studies or practices conservation, but it represents an important shift in objectives and the means employed to achieve them.

In our target sites the forest is a complex landscape which has thrived for millennia in tandem with local and Indigenous communities. Indeed, it is the intimate relationship that these people share with the forest which has produced the rich biodiversity and dense tree cover that are now recognised as so globally valuable. These communities, particularly the hunter-gatherers, cannot achieve good health without a healthy forest, and the forest will not be healthy without the communities. Why? Because evidence from around the world shows that when Indigenous communities’ forest land rights are recognised, they are the best at protecting biodiversity and promoting thriving forests (e.g. Fa et al., 2020; Dawson et al., 2024). Where communities are forcibly evicted and excluded, vital human-forest relationships are lost and illegal activities increase – threatening forests. Our project aims to secure human, animal and forest health in Cameroon and Central African Republic as one interrelated system.

Beginning with a 1-year preparation phase from September 2022, we visited communities in each of the three landscapes to assess the situation on the ground alongside local colleagues and community-based organisations. Together we planned out the different work packages and activities for the next 5 years.

Together, we decided that the project will revolve around five main actions:

- Datahub – Establish an online datahub for the participatively collected forest data and other mapped information about the condition of the forest.

- Indigenous areas – Work to demarcate and establish Indigenous conservation areas in the forms of OECMs, Territories of Life, or Biocultural Heritage Territories

- Community wellbeing – Implement mobile healthcare clinics in communities, support agriculture and forest harvesting, and restore forest through community-led tree planting

- Monitor disease – Design a participative early-warning-system with communities and advanced genetic testing labs to monitor and prevent potential zoonotic disease outbreaks

- Policy – Influence policy-making at national, regional, and international levels

Our mobile technology Sapelli, which uses a very easy picture-based interface to empower any community to collect data which is important to them, will be our major contribution to the project alongside our expertise in consulting hunter-gatherer communities about their lives and their forests in a meaningful and ethical way (e.g. blog post).

Through conducting approximately 4 months of fieldwork a year for the first few years, we will engage a total of 21 villages – 7 in each landscape – in discussions on their current situations, their relationships to the forest, to forest managers and to other forest users, and their hopes and priorities for their futures. The answers to these will feed into a process of co-designing versions of the Sapelli app with groups of women and men in each village in relation to establishing Indigenous-managed conservation areas and monitoring disease transmission in the forest. What’s more, we will collaborate closely with Project Bwanga to enable Indigenous healers to treat sick community members using simple drugs, managed through specially-designed Sapelli apps which allow them to keep track of medicines and raise the alarm if new, unknown illnesses arise – these could be an early warning for the next pandemic after all.

We’re excited for a unique part of our work in the project – organising ‘sharing sessions’. In tandem with the community-led forest restoration, we will empower community members to come together and revitilise their traditional knowledge around these trees, the animals they interact with, and the wider forest environment, as well as the remarkable spiritual culture which holds all of this knowledge together. Much of this knowledge amongst the BaYaka is transmitted through lìkànò (stories) and bè or massana (spirit dances).

The project seeks to shift conservation practice to consider the health of all forest dwellers. We hope to shift conservation activity to be dominated by bottom-up, community-led processes rather than the top down exclusionary protected area model, and for this, traditional knowledge systems must be strengthened.

We will provide (semi) regular updates on this blog and on Simon’s personal blog. You can find the project website here (work in progress!).